This little blog holds to the principle (doubtless a political principle in itself) that the morals of a composer and the awfulness of his beliefs are all very interesting but will not be discussed here. They can be read about elsewhere. Only the music will be discussed at Serenade to Music (as serenades aren't meant for deep philosophical argument). It's very difficult to hold to this principle while discussing Soviet music, however, as the whole field is strewn with countless politically-charged mines - mines people keep insisting on laying. The so-called 'Shostakovich Wars' - an insanely heated squabble over Shostakovich's presumed political opinions - show this danger at its clearest. So much bile has been wasted by critics over the issue. It comes to something when reviewers in some of the most prestigious music magazines give the strong impression of preferring to write about the booklet notes accompanying a new CD (giving their writer an ideological kicking wherever necessary) rather than giving us their considered judgement on the music and the quality of the performance.

That said, I shall now dip a little toe into these murky waters and say that the former 'good boys' of Soviet Music - those who wrote and enforced the conformist music demanded of composers by the authorities in the USSR (especially at certain periods) - now appear to be largely seen as the 'bad boys' and, as a result, find their music dismissed and ignored. The most controversial of these one-time 'good boys' is

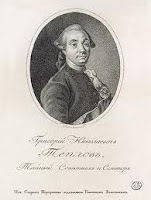

Tikhon Khrennikov, born 100 years ago this year, dying as recently as 2007 - a man whose long life encompassed the rise and fall of the Soviet Union, with room to spare. Stalin made him the all-powerful Secretary of the Composers' Union in 1948 (the year of the infamous decree denouncing many of the country's best-known composers for 'formalism'), a post he retained until 1992 (following the collapse of the Soviet Union).

Wikipedia's (largely unsympathetic)

entry on him will give you a flavour as to why he is so controversial - and two contrasting obituaries (one broadly sympathetic, one unsympathetic) can be read

here (from

The Economist) and

here (from

The Daily Telegraph).

Having made those concessions to political concerns, the questions I feel much happier dealing with now loom up, enticingly: What sort of composer was Khrennikov? Did he produce nothing but conformist hack-work? Is he a 'bad composer', unworthy to be heard? Is he unfit to wipe the boots of Shostakovich, Prokofiev & Co., musically-speaking? Ah, bring on the music and let's judge for ourselves!!

My first port of call was the 1959

Violin Concerto No.1, Op.14. Let me say straight away that I liked the piece. There's not a lot to

dislike about it. To give it its full title, it's his

Violin Concerto No. 1 in C major opus 14 - and that 'in C major' tells you that this concerto is going to be resolutely tonal music. It's also highly traditional in structure and feel, with solo writing that is firmly within the familiar virtuoso manner (including old-style cadenzas). Khrennikov's opening

Allegro con fuoco contains two main themes. The first is fast , optimistic and open to passionate restatement, with more than a tinge of Prokofiev about it - the sort of tune a giddy Juliet might dance to. It isn't quite in the same league of melodic memorability as Prokofiev, but it's not bad. Nor is the second theme, which is sweetly lyrical and 'oriental' in character - the sort of folk-like melody Russian composers had been writing (to the delight of their admirers) for generations; indeed, I think it's a clear descendant of such things as Rimsky Korsakov's

Song of India. The scoring, again, has something of Prokofiev about it. The working-out is conventional but enjoyable, with cymbals crashing away in the coda. The central

Andante espressivo is another outpouring of sweet, affecting lyricism - its romantic sweetness tempered (as it so often is in Prokofiev's music) by touches of cool fantasy in the orchestral accompaniment and an occasional, very slight dryness of harmony. That sweetness isn't tempered very much though and the impression given is of heart-on-sleeve stuff - or at least music that

sounds like heart-on-sleeve stuff. Fleeting orientalisms and Prokofievisms add to the movement's considerable charm. If it's kitsch, it's first-rate kitsch. The closing

Allegro agitato is old-fashioned piece of virtuoso showmanship, guaranteed to bring the violinist plenty of applause at the concerto's end. There are two themes again - the first fast and (as the marking suggests) agitated (albeit in an optimistic, Soviet way), the second lyrical and once more flavoured with 'oriental' colouring. If you like the lighter side of Prokofiev's music, you should like this. I do.

Was Khrennikov versatile enough to write something different in his other concertos, or do they all sound like Prokofiev with added sweeteners? Well, his

Cello Concerto No.1 in C major, Op.16 of 1964, for one, is certainly cut from much the same cloth as the

First Violin Concerto. If you like one you'll surely like the other. In three movements, its opening

Prelude opens with a gentle if passionate outpouring of lyricism from the soloist, set against various counter-melodies and an insistent if unobtrusive throb. The strain of lyricism on offer here is much the same as that found in the violin concerto, with an 'oriental' turn-of-phrase in the main melody that is strikingly similar to the 'hook' of the second subject in the first movement of the earlier piece. This may be a Khrennikov fingerprint. After this lovely start, the second movement keeps to the

Prelude's 'Andante' marking and is even more lyrical in character, with no trace of 'orientalism' to be found anywhere. It bears the title

Aria and brings forth a flow of warmly expressive melody. The mood may initially surprise you in that it takes us away from straightforward Soviet optimism into something rather more wistful and inward-sounding. Khrennikov adheres to his own principles, however, and refuses to indulge in fruitless introspective gloom, soon bringing into his music plenty of major-key warmth. It is another beautiful, heart-on-sleeve-sounding movement that should appeal to anyone who loves the Korngold

Violin Concerto. (The tunes aren't as memorable though). The closing

Sonata, the most lively movement (an 'Allegro'), brings more tunefulness and some opportunities for audience-pleasing display from the soloist - though fireworks aren't really the order of the day here any more than they are in the concerto as a whole. There is a little Prokofiev-style garishness (and even dissonance) from the orchestra in this movement, but the soloist remains essentially a singer of melodies.

Had his style changed by the time of the

Cello Concerto No.2, Op.30 of 1986? Well, there are certain differences. For starters, there are only two movements. There's also no key marking in the title and the ruminative opening suggests that the composer might be about to venture into harmonic territory he had previously forbidden (not just himself but every other Soviet composer too). He doesn't, but his harmonic palette is certainly a little wider here. That opening passage has a strong flavour of Shostakovich for example. Still, the essence of Khrennikov's music remains much as it was in the earlier works. Lyricism certainly stays as a constant feature and this

Adagio first movement is soon pouring out a stream of expressive melody, strongly rooted in rich tonal harmonies - and sounding far more romantic than the sort of melodic writing you tend to find in Shostakovich's music. There are dramatic passages and some virtuoso passage work for the soloist, but the singing of melodies is the movement's main motivation. There are some lovely movements. The second movement

Con Moto has plenty of Prokofiev-style action in its fast sections and is more openly virtuosic in character but, as you may be beginning to expect by now, there are lyrical passages too. I wouldn't class this movement as being so involving, just as I wouldn't say that this short concerto is enjoyable as its earlier counterparts, but it isn't unengaging.

None of these three works scorches its way into the gut and the memory in the way that Prokofiev's two great violin concertos or Shostakovich's equivalent concertos do. Khrennikov is undeniably a lesser composer than either of those two mighty figures of Russian music. He isn't a negligible figure though and I'm sure many of you will find all three of these concertos to be highly attractive pieces and will be as pleased as I've been to encounter them.

What though of the old apparatchik's symphonies? The first one I encountered was his final effort, the

Symphony No.3 in A major, Op.22 of 1972. It is the best thing I've yet heard by Khrennikov. It starts with a very energetic fugue that demonstrates the composer's ability to sound a bit like Prokofiev and a bit like Shostakovich while being himself. Far from being an anaemic, academic fugue, it's a somewhat grotesque-sounding jaunt. If it were by Shostakovich, you'd suspect irony and subversion. Being by Khrennikov, it ain't irony or subversion. It's absorbing stuff though. The central

Intermezzo is strange and rather beautiful. It contains an ethereal theme that, surely by coincidence, sounds like a prominent theme from Shostakovich's

Fifth Symphony slowed down, placed high in the violins and made to sound like a tune from a Prokofiev ballet. The central climax is splendidly dissonant in much the same way as Prokofiev's dissonant climaxes in

Romeo and Juliet are splendid. This movement is where the composer's bias towards lyricism blossoms and his scoring is full of imaginative details, such as the poetic ending (shades of Prokofiev's

Cinderella). The

Finale sets hectic toccata-like music, marked out by the prominent use of the xylophone, around a rather mysterious central lyrical passage. A fine piece I believe it will repay your time getting to know.

As will its predecessor. Though the first movement was written before the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, the bulk of the

Second Symphony in C minor, Op.9 was composed during the Great Patriotic War. This is a big, traditional symphonic statement, opening with an

Allegro con fuoco that combines heroism, high spirits and idyllic lyrical visions. This is, I assume, a vision of Stalin's glorious Soviet Union before Hitler went and spoiled the party by invading, though there are anticipations of the war sorrow and fighting to come. Intriguingly, the climaxes show the residual influence of Tchaikovsky. The lovely second subject is the lyrical one, with characteristic sharpened notes (redolent of folk-music). The following

Adagio is said to be an evocation of the suffering caused by the invasion, though it clearly doesn't set out to wrench the listener's emotions in the way that other such symphonies might, sounding regretful and stoical rather than despairing and angry. Again, I would note that the spirit of the 'pathetic' Tchaikovsky is not too far away, with a smidgeon of Prokofiev in some of the orchestration. It is melody-driven and essentially lyrical. The ending may remind you a little of the ending of the equivalent movement in the

A major Symphony. If that movement wasn't quite what you'd expect from the description of what it was intended to evoke, then the third movement Allegro

molto sounds even further removed from what it is said to evoke - the fight against the Nazi invaders. Such a description might lead you to expect something full of fire and desperate energy. What you get instead is a colourful, somewhat balletic scherzo that makes a generally good-natured, occasionally slightly grotesque yet overall utterly charming impression. Only the closing bars sound remotely war-like. The final

Allegro marziale looks forward to victory and is much more like what you would anticipate from such a description, with lots of brass and percussion, marching rhythms and tattoo-like figures. Still, scherzo-like episodes that seem to hearken back to the preceding movement and lyrical asides add unexpected aspects to the movement, though the music swiftly reverts to heroic battle music. For a serious wartime symphony, it's an unexpectedly entertaining affair. That presumably was what Khrennikov intended it to be, to lift his listener's spirits at a time when they most needed lifting.

Two fine symphonies then - not the equal of the best of the Shostakovich and Prokofiev symphonies, obviously, but worthy of an occasional outing (if your scruples about the man don't get in the way).

I've not yet heard the

First Symphony, Op.4 of 1933-5, but for a flavour of early Khrennikov there's always his

Piano Concerto No.1 in F major, Op.1 of 1932 - a work that is full of youthful high spirits and virtuosity. Some of the cheek of early Prokofiev and early Shostakovich finds its counterpart here, though there's that impulse to lyricism already present and correct in the central

Andante (along with the odd 'oriental' turn of melodic phrase). For a work written by a man on the verge of his twentieth birthday, it's a convincing and attractive piece of writing. It many ways, this is a different type of concerto to those for strings with which this post began. There

is versatility in Khrennikov's art.

By the time of his 1972

Piano Concerto No.2 in C major, Op.21 the virtuosity found in the

First Concerto returned with a vengeance. It begins as an extended cadenza for the soloist, building contrapuntally towards an exciting torrent of sound. The climactic passage brings in the orchestra in a blaze of C major, with an off-key note ringing out against it like a bell. The strings bring out the composer's characteristic sharpening and flattening of the melodic notes of a romantic, lyrical tune but the bell effect returns, with real bells, to wonderful effect to bring the

Introduction to a dramatic conclusion. The central

Sonata is a tradition piano-versus-orchestra conflict, full of dramatic energy. Again, we seem to be in a different place from the string concertos. There is still a feel of Prokofiev about the music though, yet it's the toccata-like, driven side of Prokofiev that is recalled here. It's not all sound and fury, as there's a scherzo-like central episode to enjoy - though that quickly sounds out furiously too. It's an exciting roller-coaster ride of a movement. Where's the lyricism? A Khrennikov work without page after page of lyricism? Surely not! But yes!! The closing

Rondo keeps to the spirit of energetic élan found throughout the concerto as a whole, though it does so in a more cheerful manner, with some of the cheek from its predecessor concerto returning. Towards its close (and after another cadenza) the climactic music from the first movement returns and brings the piece to a rousing close in true cyclic fashion. What a fine piece this is!

There's another one to go. (I've not yet heard the

Fourth Piano Concerto of 1991). The

Piano Concerto No.3 in C, Op.28 from 1983-4 is a slightly lighter affair than the

Second. The opening music reminds me somewhat of the gamelan-style music from the end of the first movement of Poulenc's delicious

Double Piano Concerto. I wonder if Khrennikov had it in mind. After the woodwinds echo it most attractively, the piano introduces a lyrical melody of the kind we have grown to expect from our composer, though its continuation again has a surprising amount of Poulenc about it. Much of this passage is for the piano alone, though the woodwinds get the tune shortly after. The mood shifts again to something more boisterous and garish before we are swung into a spot of cheeky neo-Classical charm...and so on. Who else composes like that? Poulenc. (I think I'm onto something here and I bet you can guess what it is!). After such an entertaining movement, the listener must have high hopes for the central

Moderato. They are mostly met. It takes the form of a slow, lyrical waltz - a

valse triste, so to speak (though as ever with this composer, it's not especially

triste) - at least to begin with. Cadenza-like passages for the pianist, however, carry us away from this initial music and the opening theme returns transformed into something loud and brash. The movement has moved somewhere very different. The piano tries to assuage the violent mood that has entered the music and the music drifts away in a spirit of hesitant lyricism, poetically. The closing

Allegro is closer in spirit to the

Second Piano Concerto than either of the other two movements and brings the work to a bravura close, with a few surprises along the way.

All three of these Khrennikov's piano concertos would prove a pleasant experience for concert-going and home-staying listeners alike. Will the man's bad name stop this from happening any time soon?

For Khrennikov on a smaller scale, there's the

Cello Sonata, Op.34 from 1989. The main melody of the opening

Andantino has a variation on that little 'oriental' melodic hook found in the

First Violin Concerto and the

First Cello Concerto. The movement as a whole has other elements those of you who have followed me through the composer's music will recognise from other pieces, but it's none the worse for that. The piece will strike a particular chord with those whose favourite side of Khrennikov is that found most conspicuously in his string concertos. The central

Andante is soulful-sounding and lyrical while the closing

Allegro is lively and tuneful.

Among other treats from Tikhon Khrennikov to be found on

YouTube, I expect you'll enjoy his

Song of the Drunks from the incidental music to

Much Ado About Nothing, Op.7 from 1935-6), and how about his

Five Romances for voice and piano after Robert Burns, Op.11 from 1942?

So, what do you make of the music of this extremely controversial figure? Attractive, isn't it? Would you have preferred it to have been complete rubbish?